BLOG POSTS

Review - Amber, Gold & Black - The History of Britain’s Great Beers

This book by Martyn Cornell describes itself in the introduction as a "celebration" of British brewing, and in the title as "the history of Britain's Great Beers", but it's not really that - not exactly. It is, however, crammed full of names and dates and figures and brands and gravity readings, so much so that they tend to spill out onto the table and floor as you are reading them. Did you know that the Free Mash Tun Act was passed in 1880, enabling brewers to once again brew with ingredients other than malt? In 1862-63, Edinburgh brewer William Younger sold four types of Scotch Mild Ale to.... but there they go again, getting all over the place, and how am I going to clean all these bloody facts up?

As I read this I began to wish for more stories, details about the characters involved, insight into what it all meant historically, nationally, internationally, scientifically, religiously. I prefer my history more anecdotal than is Cornell's style. For a while there I was thinking that he wouldn't even include one of my favourite stories, about the explosions that occurred in several early brewing factories as industrial brewers scaled up. (He does: he modestly describes it as "the barrels grew bigger and began to burst" - I'll say! In one incident he describes, four houses were wrecked and eight people killed!)

There is definitely some good stuff in here.We hear how porter brewers, to achieve the characteristic black colour, would often adulterate brews with ingredients like molasses or liquorish. Cornell describes how 19th century brewers would use the practice of "gyling", adding fresh wort to partially- or wholly-fermented wort, giving it a youthful sparkle, and thereby achieving an early form of carbonation. The account of the original IPAs was especially interesting: as the East India Company took ales on a long sea journey from Britain to India,

..the slow, regular temperature changes on the journey and the rocking it received in the oak casks that it sat in had a transforming effect. The beer arrived in India with the maturity and depth of flavour previously only found after years in a cellar and the Indian expatriates loved it.

Now try recreating that style in your brew fridge!

One problem I have with these sort of histories is that they tend to view history backwards, starting with how things are today and then working back. Perhaps this is inevitably given how Cornell has structured his book, each chapter being devoted to a particular style. IPA is a fantastic style, justifiably popular - but why does it get a chapter and not, say, Pale Ale? Similarly, there is the inevitable chapter on herb beer, though we might ask the obvious question - how did 'herb' beer become a sub-category of 'hopped' beer? (Randy Mosher, in his book Radical Brewing, at least titles his herb-brewing chapter Hops are just another herb, man.)

On the other hand, Cornell chronicles several obsolete beer styles in fine detail - (though can a beer style be both "Great" and dead at the same time?) The chapter on wheat beers - once hugely popular in Britain, though banished to obscurity and, finally, extinction by a 17th century law - was a revelation for me. The wheat beer style, as Cornell explains, had little to no hops, was drunk quite fresh - and fermentation was kicked off with 'grouts', biscuits made from flour and egg whites! "Mum" - though perhaps originally received from the continent - is perhaps another lost British wheat beer; Cornell includes a quote from Samuel Pepys having a drink at the "Mum House" - possibly the last era in history when "Mum" and "alcohol" was so felicitously combined.

There are few proper recipes or tables, but this is less a book for the common reader than for the brewer. Packed full of details like gravity readings and grain amounts, Cornell's book seems aimed at someone who wants to find out more about a historical style. Cornell's knowledge is precise and I have few quibbles. The most serious, perhaps, is with his speculation that mead began when people discovered hives with "naturally produced" mead - a doubtful proposition; bees are naturally hygienic and do everything they can to ensure nectar doesn't ferment - honey has been discovered in tombs that has been preserved, without fermenting, for thousands of years.

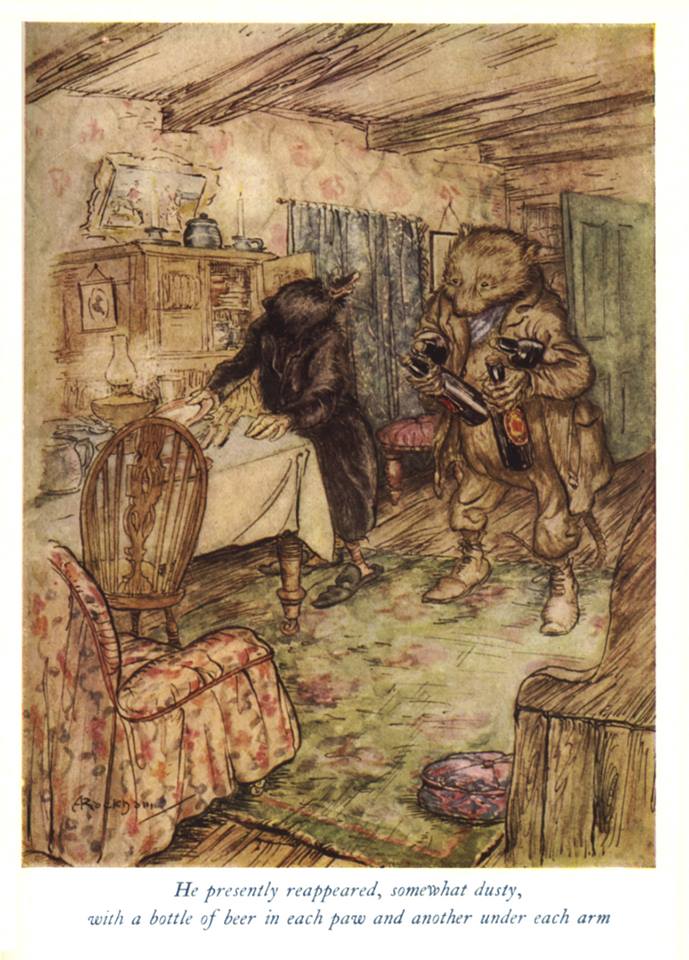

Mostly, though, I got picky with Cornell's quotes from literature. For instance, why reference one of the most dismal and dreary books in history, Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, in the introduction to the chapter on mild ales? On the other hand, I was charmed by the quote from Wind in the Willows, where Ratty finds a bottle of the very strong Burton Ale in Moley's cellar:

'I perceive this to be Old Burton,' he remarked approvingly: 'Sensible Mole! The very thing!'

Take note, kids!